Thursday, December 27, 2012

D-Town Farm: Donate to DBCFSN! DBCFSN Year End Solicitation L...

D-Town Farm: Donate to DBCFSN! DBCFSN Year End Solicitation L...: Dear Supporter of Food Justice: The Detroit Black Community Food Security Network (DBCFSN) has worked tirelessly for nearly se...

Sunday, December 16, 2012

D-Town Farm: DBCFSN Year End Solicitation Letter.

D-Town Farm: DBCFSN Year End Solicitation Letter: Dear Supporter of Food Justice: The Detroit Black Community Food Security Network (DBCFSN) has worked tirelessly for nearly sev...

Donate to DBCFSN! DBCFSN Year End Solicitation Letter.

Dear

Supporter of Food Justice:

Dear

Supporter of Food Justice:The Detroit Black Community

Food Security Network (DBCFSN) has worked tirelessly

for nearly

seven years to contribute to the public dialogue about, and practice of, food

security and food justice in Detroit. We continue to operate innovative programs

that grow fresh produce, train urban farmers, sell food cooperatively,

influence public policy, engage youth and address racism within the food

system.

Among our

many significant milestones achieved in 2012 were:

• Completion

of feasibility study for the expansion of our co-op buying club to a full service

retail food co-op store

• Installation of water lines and

frost-free hydrants at D-Town Farm

• Implementation of our first Summer

Urban Ag Internship Program

• Awarded

a $10,000 grant from Food Co-op Initiative to conduct community education and engagement

sessions on our food co-op

• Expanded

our 6th Annual Harvest Festival to two days and featured keynotes by

Urban Ag Guru Will Allen and Vegan Chef Bryant Terry

• Received the James Beard Foundation

Leadership Award

• Provided

leadership and helped to frame the issues in the struggle for land justice in

Detroit

We are

asking our friends and supporters to make a generous year-end donation to the

Detroit Black Community Food Security Network to help us deepen and broaden our

on-going work of building food justice, food security and food sovereignty for

Detroiters. We

appreciate all donations from $10 to $10,000. DBCFSN is a 501c3 non-profit, so

all donations are tax deductible. Your generous donation will help us continue

making progress towards achieving our goals.

Donations

can be made on-line at our website (www.detroitblackfoodsecurity.org), or can

be mailed to:

Detroit

Black Community Food Security Network

3800 Puritan

Detroit, MI

48238

We

appreciate your support and look forward to the opportunity to continue serving

our community in the upcoming year.

Respectfully,

Malik Yakini, Executive Director

Sunday, December 9, 2012

D-Town Farm: Actor Danny Glover joins Detroit protest aganst Ha...

D-Town Farm: Actor Danny Glover joins Detroit protest aganst Ha...: Actor Danny Glover joins Detroit land protest » 6:01 PM - Actor Danny Glover joins Detroit land protest » Local 4's Bisi Onile-E...

Actor Danny Glover joins Detroit protest aganst Hantz Group attempt Land Grab!

Wednesday, December 5, 2012

D-Town Farm: Danny Glover speaking at a meeting this Saturday,D...

D-Town Farm: Danny Glover speaking at a meeting this Saturday,D...: The battle for land justice heats up further with actor/activist Danny Glover speaking at a meeting this Saturday organized by Detroite...

Danny Glover speaking at a meeting this Saturday,December 8, 2012, 6:00 - 8:00 p.m. at Timbuktu Academy of Science and Technology, 10800 E. Canfield, 1 block east of French Road, Detroit, 48214.

The

battle for land justice heats up further with actor/activist Danny

Glover speaking at a meeting this Saturday organized by Detroiters

opposed to the proposed sale of more than 1500 City owned lots to John

Hantz. The meeting will be held Saturday, December 8, 2012, 6:00 - 8:00

p.m. at Timbuktu Academy of Science and Technology, 10800 E. Canfield, 1

block east of French Road, Detroit, 48214. Spread the word!!! We need a

heavy turnout by those living on Detroit's lower east side.

Tuesday, November 20, 2012

D-Town Farm: Hantz Farms Deal, Controversia...

D-Town Farm:

Hantz Farms Deal, Controversia...: Hantz Farms Deal, Controversial Land Sale, To Go Before Detroit City Council Category: Breaking News Publish...

Hantz Farms Deal, Controversia...: Hantz Farms Deal, Controversial Land Sale, To Go Before Detroit City Council Category: Breaking News Publish...

Hantz Farms Deal, Controversial Land Sale, To Go Before Detroit City Council

Category: Breaking NewsPublished on Tuesday, 20 November 2012 09:00 Written by Huffington Post

The name Hantz Farms conjures up strong reactions from many Detroiters -- especially those involved with the city's urban agriculture movement. After nearly four years the controversial development project, originally envisioned as the world's largest urban farm, is scheduled to go before Detroit City Council on Tuesday.According to Marcell Todd Jr., director of Detroit's City Planning Commission, if approved, the Hantz deal would be "the largest speculative land sale in the city's history." In its current form, the proposed transaction involves the sale of about 1,500 parcels -- roughly 140 acres of land -- on the city's east side to John Hantz, Detroiter and financial services magnate, through Hantz Woodlands, a division of Hantz Farms. The proposed area would lie roughly between Van Dyke and St. Jean Street and Jefferson and Mack Avenue.

The businessman is seeking to transform the area into a mixed hardwoods timber farm, pending the approval of a city urban agriculture ordinance, but has also indicated a willingness to purchase and maintain the land simply in order to make the area more livable. Despite these changes, the issue remains as contentious as it has ever been. While some see the project as boon to a blighted neighborhood, others feel the businessman is receiving special treatment and worry about its long-term implications.

The Bing administration has pushed to have the deal processed as a simple purchase agreement, but members of council's Planning and Economic Development Committee have asked for a more detailed plan. Last Thursday during a meeting of the committee, Council members Saunteel Jenkins, Kenneth Cockrel Jr. and Kwame Kenyatta decided to put the measure up before the full council, but requested that it be submitted as a development agreement with a reverter clause allowing the city to back out, if the company violates the terms of the deal.

"I support having someone come in and buy these properties who will clean them up, who will keep them up, even plant trees," said Councilwoman Jenkins. "[But] if the agreement is not to my satisfaction Tuesday, if it's up for a vote, my vote is no."

Councilman Cockrel said although he has received a deluge of phone calls and emails both for and against the deal, he was concerned there was a perception of unfair treatment, noting that the Bing administration seemed to be proceeding with the Hantz Farms transaction despite promises it would hold off on urban agriculture developments until an ordinance was passed.

Edith Floyd, a Detroiter who's been farming for nearly 40 years, was less measured in her feelings.

"He's getting a special deal. The city is not treating us fair at all," she told The Huffington Post.

Floyd maintains 32 lots on the city's east side, operates a greenhouse and runs a small business called Farming in the City. Although she eventually got a temporary permit for her greenhouse, she said that the city didn't make it easy for her. She thinks the city should be selling the land to people like her who have already been taking care of city lots.

"People with money can buy whatever they want and do whatever they want, but other people can't do it," she said. "It's two laws: one for the rich and one for the poor."

Greg Willerer and his wife Olivia run a one-acre farm called Brother Nature in Detroit. He told The Huffington Post there is widespread opposition to the Hantz deal among those involved with Detroit's urban agriculture movement.

"I don't know of anyone who's supportive of it," he said. Like Floyd he believes the city needs to support smaller farmers who grow food for their livelihoods.

"It's really insulting. It's really frustrating. We have huge amounts of land, and the city could sell a lot of this land for farming. If you're not going to sell us the land, at least give us the land to lease for ten years."

Citing the example of the Birdtown Community Garden, which was recently destroyed to make room for a local business, Willerer said he felt Detroit's power brokers tend to see urban gardens only as placeholders for other types of development.

"They still want Detroit to be this Chicago-type city. It's not and it never will be," he said. "There's a vibrant food system and it's kind of exciting to see all this change going on. The city should help us or get out the way."

Others like Malik Yakini of the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network are concerned about the long-term power dynamics of the deal.

"As we struggle to foster food security, food justice and food sovereignty the question of land, who 'owns' it, who controls it, and who benefits from it, must be in the forefront of our discussions," he said in a recent Facebook post.

Hantz Farms president Mike Score told The Huffington Post that the primary purpose of the deal is to improve the community. He said his company plans on demolishing abandoned structures, mowing the grass, removing trash and debris, planting trees and paying taxes on the property.

"We'll make the neighborhood more attractive, more livable and, then, also, by eliminating the publicly-owned blight, the private property increases in value."

As for those who say the deal is a land grab or that Hantz Farms is getting special treatment, he says they're mistaken.

"It's not been an easy process, but we're not complaining," he said. "We've been negotiating for four years and the expenses have been significant -- and if that's special treatment, then I feel sorry for everybody else."

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/11/19/hantz-farms-deal-land-detroit-council_n_2159863.html?utm_hp_ref=detroit

Wednesday, November 14, 2012

D-Town Farm: Detroit: A Tale of Two... Farms?By HuffPost's si...

D-Town Farm: Detroit: A Tale of Two... Farms? By HuffPost's si...: Detroit: A Tale of Two... Farms? By HuffPost's signature lineup of contributors Eric Holt Gimenez: Executive Director, Foo...

D-Town Farm: Detroit: A Tale of Two... Farms?By HuffPost's si...

D-Town Farm: Detroit: A Tale of Two... Farms?By HuffPost's si...: Detroit: A Tale of Two... Farms? By HuffPost's signature lineup of contributors Eric Holt Gimenez: Executive Director, Foo...

Detroit: A Tale of Two... Farms?

By HuffPost's signature lineup of contributorsEric Holt Gimenez: Executive Director, Food First/Institute for

Food and Development Policy

Detroit: A Tale of Two... Farms?

A recent article in The Wall Street Journal

celebrated the Hantz Farms project to establish a 10,000 acre private

farm in Detroit. The project hinges on a very large land deal offered by

financial services magnate John Hantz to buy up over 2,000 empty lots

from the city of Detroit. Hantz's ostensible objective is to establish the world's largest urban mega-farm.

I say "ostensible" because despite futuristic artists' renderings of

Hantz Farms' urban greenhouses, presently John Hantz is actually growing

trees rather than food. The project website

invites us to imagine "high-value trees... in even-spaced rows" on a

three-acre pilot site recently cleaned, cleared and planted to hardwood

saplings. These trees, it seems, are just a first step in establishing a

200 acre forest and eventually -- pending approval by the City Council

-- the full Hantz megafarm. In the short run, the purchase by Hantz cleans things up, puts foreclosed lots back on the tax rolls and relieves the city of maintenance responsibilities. If the tree farm expands, it could provide a few jobs. In the long run, however, Hantz hopes his farm will create land scarcity in order to push up property values -- property that he will own a lot of.

The Hantz Farms project openly prioritizes creating wealth by appreciating real estate rather than creating value through productive activities. If successful, the urban mega-farm will clearly lead to an impressive accumulation of private wealth on what was public land. It is less clear what this will mean for the low-income residents of Detroit.

Despite two years of glowing national press coverage, not all is going smoothly with the project. Under Michigan's Right to Farm Act, the Hantz megafarm would pass from the jurisdiction of the city to that of the state. Many in the city are reluctant to lose control over such a big chunk of real estate. When friction on the issue developed between the Administration, city offices and the public, the Hantz negotiations moved quietly out of the public spotlight. But the wheels kept turning...

In a June memo to the Detroit City Council, the City Planning Department complained that:

The potentially massive transfer of public assets to private ownership (at a cleanup cost of $2 million to the city) has led many residents to call the Hantz deal a "land grab."

It has come to our attention, due to inquiry from the media, and communication from a representative from Hantz Farms that the Administration is proposing to sell property to Hantz Farms or some subsidiary for a project on the east side of Detroit. Our office has not received any formal information from the Administration regarding such a proposal; therefore, we do not know with certainty the scope of the project or whether or not it complies with current zoning and/or other City codes.

Though the scale is unprecedented, does this real estate project really have anything in common with the brutal, large-scale land acquisitions sweeping Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America?

Land grabs in far-off places occur when governments allow outside investors to push subsistence farmers and pastoralists off massive swathes of tropical farm and range land to establish mega-plantations of palm oil or sugarcane for ethanol. Despite the hype, very few of these projects actually grow any food. Often the land grab is simply about investing in real estate. Researchers studying the global phenomena have not yet found any benefits for local communities resulting from these land grabs. On the contrary, uprooted from land and livelihoods, poor rural people are forced into the option of last resort: migration.

Notwithstanding, from Goldman Sacks and the Carlyle Group to university pension funds, holders of big money are anxious to put their wealth into land, at least until the global recession blows over. Cheap land, devalued by economic and post-industrial recessions, is literally up for grabs. Once acquired, the easiest and most effective, low-cost way for big financial dogs to quickly mark their newly-acquired territory has been to plant trees -- trees require little maintenance and if global carbon markets ever really kick in, could pay dividends.

As Susan Payne, CEO of Emergent Asset Management has bluntly stated, "In South Africa and sub-Saharan Africa the cost of agriland, arable, good agriland that we're buying is one-seventh of the price of similar land in Argentina, Brazil and America. That alone is an arbitrage opportunity. We could be moronic and not grow anything and we think we will make money over the next decade."

Whether the objective is to safeguard wealth, speculate on real estate, accrue water rights, bet on carbon credits or actually plant food or fuel crops, the point of a land grab is to leverage financially-stressed governments in order to acquire large areas of public land under a convenient global pretense (e.g., cooling the planet, feeding the world or ending the world fuel crisis). This supposedly benefits the planet by enriching few and impoverishing many. Detroit's 2,000 city-owned lots (now on sale at $300 each), coupled with a food security discourse, fits some of the land grab parameters.

But like most places around the world, there are people living in the land of Detroit, and not all residents are happy with Hantz's plan -- which is probably why he has worked behind the scenes, avoiding Detroit's Urban Ag Work Group, the City Planning Commission, and the Detroit Food Policy Council. While some residents support the Hantz forest, others -- like those working with D-town Farms, who are already very busy growing and distributing food -- don't believe the hype. They are opposing the Hantz deal on moral, political and economic grounds. Malik Yakini of the Detroit Black Food Security Network noted that he was anxious to participate in more active opposition to this land grab, and that given the Administration's disregard for the work of the Urban Ag Work Group and the City Planning Commission, the sale of the land to Hantz undermines real democracy.

These are strong words coming from one of Detroit's leading food security advocates. When one looks at the trajectory of D-Town Farms and the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network, what appears as indignant opposition is really a fundamentally different logic for addressing the health, education and general welfare concerns of Detroiters living in the underserved neighborhoods the city refers to as blighted neighborhoods.

The Detroit Black Community Food Security Network is a coalition of community groups that focus on urban agriculture, policy development and co-operative buying. They have been farming in Detroit since 2006, pioneered an 18-month effort to formulate a city-wide food policy adopted by the City Council in 2008, and researched and proposed the model for the current Detroit Food Policy Council. They have helped grow an extensive network of gardens and buying clubs to address fresh food access and employment challenges in Detroit's underserved neighborhoods. Throughout, the Network held public meetings and worked extensively with city leaders, local business, churches and neighborhood organizations, as well with Wayne State and Michigan State University. The seven acre D-Town Farm is a hub in an extensive community-based effort to turn the local food system into an engine for local economic development, owned and operated by those who are most adversely impacted by the lack of fresh food access in Detroit's underserved neighborhoods.

But recognizing that Hantz Farms follows a speculative and private real estate logic and seeks to concentrate wealth, while D-Town Farms follows a community livelihoods logic that seeks an equitable distribution of opportunities and resources, still barely touches the surface of the deep differences in demography, culture, socio-economic status and political orientation of the two urban farming projects.

At the center of this tale of two farms, lies a contentious global question just beginning to resurface in the United States these days: the land question.

Land -- rural or urban -- is more than just land; it is the space where social, economic and community decisions are made, and it is the place of neighborhood, culture and livelihoods. It is home. Therefore, it is more than just a "commodity." While John Hantz's stated objective is to produce scarcity of the land as a commodity, residents living in the lower-income homes of post-industrial Detroit deal daily with scarcity of health, education and basic public services to which they are entitled. The transformation of these public goods into private "commodities," coupled with their scarcity has not resulted in any improvement for residents. Market demand and human needs are not the same, and one does not necessarily address the other. Driving up the price of land in underserved neighborhoods may well put the city on the road to gentrification, but it won't help solve the challenges facing the majority of Detroit's citizens.

Wednesday, October 31, 2012

D-Town Farm: Meet JBF Leadership Award Winner Malik Yakini

D-Town Farm: Meet JBF Leadership Award Winner Malik Yakini: Meet JBF Leadership Award Winner Malik Yakini by Elena North-Kelly on October 15, 2012 In our final countdown to W...

Meet JBF Leadership Award Winner Malik Yakini

Meet JBF Leadership Award Winner Malik Yakini

by Elena North-Kelly on October 15, 2012

In our final countdown to Wednesday's 2012 James Beard Foundation Leadership Awards, we're introducing you to each of the five visionaries being honored for their outstanding contributions to creating a healthier, safer, and more sustainable food world. We've already filled you in on Dr. Kathleen Merrigan, Dr. Jason Clay, and Tensie Whelan—and today, we'd like you to meet:

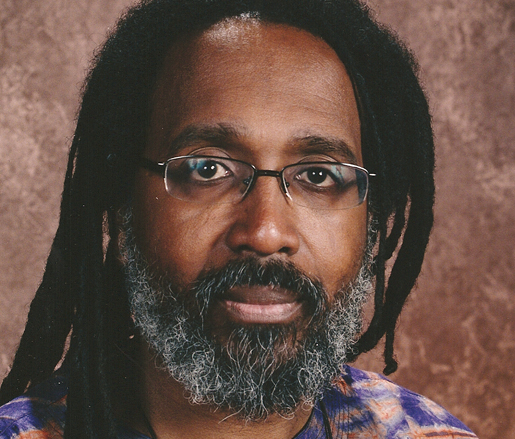

Malik Yakini

Executive Director, Detroit Black Community Food Security Network

When Malik Yakini describes the bumper crop of organic tomatoes, kale, and salad greens that he and his team harvested this year at D-Town Farm, a seven-acre site in a public park in Detroit and the largest endeavor of the DBCFSN, he isn’t simply taking pride in the produce. “The work that we’re doing is not just about food,” Yakini emphasizes. “We’re planting seeds of consciousness at the same time that we’re planting seeds that will grow into fruits and vegetables.”

For this lifelong social justice activist, transforming consciousness means promoting self-sufficiency and building a sense of community empowerment—all within the context of “traditional African cultures and our own historical legacy of resistance to oppression.” To this end, DBCFSN also runs the Ujamaa Food Co-op, a monthly buying club for obtaining groceries at below-retail prices, set to open as a full-service retail store within the next two years.

Yakini founded DBCFSN in 2006 to counter a food system that has reduced his city to what has been termed a “food desert.” Many Detroiters live nowhere near a supermarket but must obtain “what could really only nominally be called food,” he explains, from fringe food locations like gas stations or party stores. “Since we’re faced with a lack of fresh, healthy produce in Detroit, we thought growing our own food is one way of addressing that. We see ourselves as creating a model that we hope will inspire other people in the city,” says Yakini.

In the former automotive center of the world, 20 to 30 percent of residential lots are now vacant, as thousands of unsafe buildings have been demolished by the city. But rising from that rubble is a major urban agriculture movement, with Yakini as one of the significant players.

He’s also inspired by Growing Power founder and CEO Will Allen, who, in turn, admires Yakini for “his commitment to improve the lives of all the citizens of Detroit.” Says the 2011 JBF Leadership Award recipient, “Malik Yakini is truly one of the strongest community leaders in the country because he is unafraid to tell the truth.”

Yakini acknowledges that improving Detroit’s food security involves more than creating access. It also requires a cultural shift away from the emotional attachment to unhealthy food—which DBCFSN addresses with a public education campaign that includes the “What’s for Dinner?” lecture series and the Food Warriors Youth Development Program, which teaches youth about problems with the current food system and the virtues of sustainable agriculture.

DBCFSN also fosters a localized food system at an advocacy level: it’s the lead organization in writing the city of Detroit’s Food Security policy and in the 2009 creation of the Detroit Food Policy Council, which Yakini chaired until this spring.

Clearly Yakini is not slowed down by complacency. “I can’t really stop and pat myself on the back, because the majority of people in the city of Detroit are still impacted by food insecurity and food injustice.”

About the James Beard Foundation Leadership Awards

The 2012 JBF Leadership Awards recognize visionaries from a broad range of backgrounds, including government, nonprofit, and literary arts, who are working toward creating a healthier, safer, and more sustainable food world. This year’s honorees were chosen by an advisory board comprised of a dozen experts from diverse areas of expertise, as well as last year’s Leadership Award recipients. Now in its second year, the Leadership Awards recognize specific outstanding initiatives as well as bodies of work and lifetime achievement. Winners will be honored at a dinner ceremony that will take place during the James Beard Foundation Food Conference on October 17 in New York City. For more information, visit jbfleadershipawards.org.

Saturday, September 22, 2012

D-Town Farm: D-Town Farm’s Sixth Annual Harvest Festival this S...

D-Town Farm: D-Town Farm’s Sixth Annual Harvest Festival this S...: D-Town Farm’s Sixth Annual Harvest Festival "Don't forget, D-Town Farm's 6th Annual Harvest Festival takes place this Saturday, Sep...

Thursday, September 20, 2012

D-Town Farm’s Sixth Annual Harvest Festival this Saturday, September 22 and Sunday September 23 from noon - 6:00 p.m.

D-Town Farm’s Sixth Annual Harvest Festival

"Don't forget, D-Town Farm's 6th Annual Harvest Festival takes place this Saturday, September 22 and Sunday September 23 from noon - 6:00 p.m. Vegan Soul Chef, Bryant Terry, gives keynote on Saturday. Urban farming guru Will Allen gives keynote on Sunday. Vendors, farmers market, live music, learn shops on bee-keeping, breastfeeding, gardening, composting, cooking demos, children's activities, hay rides, farm tours and more. You don't want to miss this. www.detroitblackfoodsecuritynetwork.com.

|

| Will Allen, Speaker & Author of The Food Revolution |

|

| Bryant Terry, Speaker & Author of Vegan Soul Kitchen |

Posted by D-Town Farm at 6:37 PM

Wednesday, September 19, 2012

The Sixth Annual D-Town Farm Harvest Festival will take place on Saturday, September 22 and Sunday September 23 from noon – 6:00 p.m. both days. The family friendly event will feature farm tours, children’s activities, “learn-shops” on bee-keeping, breastfeeding, gardening, composting and a variety of other topics,live music, food preparation demonstrations, speakers, a farm stand and other vendors. |

|

| Will Allen, Speaker & Author of The Food Revolution |

|

| Bryant Terry, Speaker & Author of Vegan Soul Kitchen |

Wednesday, August 29, 2012

D-Town Farm: D-Town Farm HARVEST FESTIVAL, Sat.-Sept.22 & Sun. ...

D-Town Farm: D-Town Farm HARVEST FESTIVAL, Sat.-Sept.22 & Sun. ...:

This year the festival will feature and arthors' tent with book signing by a number of health and food authors including Will Allen, author of The Food Revolution, Yvelette Stines, author of Vernon the Vegetable Man, Andrea King-Collier, author of Black Women's Guide to Black Men's Health, Ray Stone, author of Eat Like You Give a Damn: Beginning Your Lifestyle Transition and Bryant Terry author of Vegan Soul Kitchen (VSK): Fresh, Healthy, and Creative African American Cuisine, and his latest book: The Inspired Vegan: Seasonal Ingredients, Creative Recipes, Mouthwatering Menus. For More info call (313)345-3663 or visit our Website at www.detroitblackfoodsecuritynetwork.com. We can also be found on facebook at Detroit Black Community Food Security Network.

D-Town Farm’s Sixth Annual Harvest Festival

The Sixth Annual D-Town Farm Harvest Festival will take place on Saturday, September 22 and Sunday September 23 from noon – 6:00 p.m. both days. The family friendly event will feature farm tours, children’s activities, “learn-shops” on bee-keeping, breastfeeding, gardening, composting and a variety of other topics,live music, food preparation demonstrations, speakers, a farm stand and other vendors.

D-Town Farm HARVEST FESTIVAL, Sat.-Sept.22 & Sun. Sept.23, 2012, NOON 'til 6PM both days

| ||||

D-Town Farm’s Sixth Annual Harvest Festival

The

Sixth Annual D-Town Farm Harvest Festival

will take place on Saturday, September 22 and

Sunday September 23 from noon – 6:00 p.m. both days. The family friendly

event will feature farm tours, children’s

activities, “learn-shops” on bee-keeping, breastfeeding, gardening,

composting and a variety of other topics,live

music, food preparation demonstrations, speakers, a farm stand and other

vendors.

|

|

| Will Allen, Speaker & Author of The Food Revolution |

|

| Bryant Terry, Speaker & Author of Vegan Soul Kitchen |

Wednesday, July 18, 2012

Detroit: A Tale of Two... Farms?

Eric Holt Gimenez

Executive Director, Food First/Institute for Food and Development Policy

A recent article in The Wall Street Journal celebrated the Hantz Farms project to establish a 10,000 acre private farm in Detroit. The project hinges on a very large land deal offered by financial services magnate John Hantz to buy up over 2,000 empty lots from the city of Detroit. Hantz's ostensible objective is to establish the world's largest urban mega-farm.I say "ostensible" because despite futuristic artists' renderings of Hantz Farms' urban greenhouses, presently John Hantz is actually growing trees rather than food. The project website invites us to imagine "high-value trees... in even-spaced rows" on a three-acre pilot site recently cleaned, cleared and planted to hardwood saplings. These trees, it seems, are just a first step in establishing a 200 acre forest and eventually -- pending approval by the City Council -- the full Hantz megafarm.

In the short run, the purchase by Hantz cleans things up, puts foreclosed lots back on the tax rolls and relieves the city of maintenance responsibilities. If the tree farm expands, it could provide a few jobs. In the long run, however, Hantz hopes his farm will create land scarcity in order to push up property values -- property that he will own a lot of.

The Hantz Farms project openly prioritizes creating wealth by appreciating real estate rather than creating value through productive activities. If successful, the urban mega-farm will clearly lead to an impressive accumulation of private wealth on what was public land. It is less clear what this will mean for the low-income residents of Detroit.

Despite two years of glowing national press coverage, not all is going smoothly with the project. Under Michigan's Right to Farm Act, the Hantz megafarm would pass from the jurisdiction of the city to that of the state. Many in the city are reluctant to lose control over such a big chunk of real estate. When friction on the issue developed between the Administration, city offices and the public, the Hantz negotiations moved quietly out of the public spotlight. But the wheels kept turning...

In a June memo to the Detroit City Council, the City Planning Department complained that:

The potentially massive transfer of public assets to private ownership (at a cleanup cost of $2 million to the city) has led many residents to call the Hantz deal a "land grab."

It has come to our attention, due to inquiry from the media, and communication from a representative from Hantz Farms that the Administration is proposing to sell property to Hantz Farms or some subsidiary for a project on the east side of Detroit. Our office has not received any formal information from the Administration regarding such a proposal; therefore, we do not know with certainty the scope of the project or whether or not it complies with current zoning and/or other City codes.

Though the scale is unprecedented, does this real estate project really have anything in common with the brutal, large-scale land acquisitions sweeping Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America?

Land grabs in far-off places occur when governments allow outside investors to push subsistence farmers and pastoralists off massive swathes of tropical farm and range land to establish mega-plantations of palm oil or sugarcane for ethanol. Despite the hype, very few of these projects actually grow any food. Often the land grab is simply about investing in real estate. Researchers studying the global phenomena have not yet found any benefits for local communities resulting from these land grabs. On the contrary, uprooted from land and livelihoods, poor rural people are forced into the option of last resort: migration.

Notwithstanding, from Goldman Sacks and the Carlyle Group to university pension funds, holders of big money are anxious to put their wealth into land, at least until the global recession blows over. Cheap land, devalued by economic and post-industrial recessions, is literally up for grabs. Once acquired, the easiest and most effective, low-cost way for big financial dogs to quickly mark their newly-acquired territory has been to plant trees -- trees require little maintenance and if global carbon markets ever really kick in, could pay dividends.

As Susan Payne, CEO of Emergent Asset Management has bluntly stated, "In South Africa and sub-Saharan Africa the cost of agriland, arable, good agriland that we're buying is one-seventh of the price of similar land in Argentina, Brazil and America. That alone is an arbitrage opportunity. We could be moronic and not grow anything and we think we will make money over the next decade."

Whether the objective is to safeguard wealth, speculate on real estate, accrue water rights, bet on carbon credits or actually plant food or fuel crops, the point of a land grab is to leverage financially-stressed governments in order to acquire large areas of public land under a convenient global pretense (e.g., cooling the planet, feeding the world or ending the world fuel crisis). This supposedly benefits the planet by enriching few and impoverishing many. Detroit's 2,000 city-owned lots (now on sale at $300 each), coupled with a food security discourse, fits some of the land grab parameters.

But like most places around the world, there are people living in the land of Detroit, and not all residents are happy with Hantz's plan -- which is probably why he has worked behind the scenes, avoiding Detroit's Urban Ag Work Group, the City Planning Commission, and the Detroit Food Policy Council. While some residents support the Hantz forest, others -- like those working with D-town Farms, who are already very busy growing and distributing food -- don't believe the hype. They are opposing the Hantz deal on moral, political and economic grounds. Malik Yakini of the Detroit Black Food Security Network noted that he was anxious to participate in more active opposition to this land grab, and that given the Administration's disregard for the work of the Urban Ag Work Group and the City Planning Commission, the sale of the land to Hantz undermines real democracy.

These are strong words coming from one of Detroit's leading food security advocates. When one looks at the trajectory of D-Town Farms and the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network, what appears as indignant opposition is really a fundamentally different logic for addressing the health, education and general welfare concerns of Detroiters living in the underserved neighborhoods the city refers to as blighted neighborhoods.

The Detroit Black Community Food Security Network is a coalition of community groups that focus on urban agriculture, policy development and co-operative buying. They have been farming in Detroit since 2006, pioneered an 18-month effort to formulate a city-wide food policy adopted by the City Council in 2008, and researched and proposed the model for the current Detroit Food Policy Council. They have helped grow an extensive network of gardens and buying clubs to address fresh food access and employment challenges in Detroit's underserved neighborhoods. Throughout, the Network held public meetings and worked extensively with city leaders, local business, churches and neighborhood organizations, as well with Wayne State and Michigan State University. The seven acre D-Town Farm is a hub in an extensive community-based effort to turn the local food system into an engine for local economic development, owned and operated by those who are most adversely impacted by the lack of fresh food access in Detroit's underserved neighborhoods.

But recognizing that Hantz Farms follows a speculative and private real estate logic and seeks to concentrate wealth, while D-Town Farms follows a community livelihoods logic that seeks an equitable distribution of opportunities and resources, still barely touches the surface of the deep differences in demography, culture, socio-economic status and political orientation of the two urban farming projects.

At the center of this tale of two farms, lies a contentious global question just beginning to resurface in the United States these days: the land question.

Land -- rural or urban -- is more than just land; it is the space where social, economic and community decisions are made, and it is the place of neighborhood, culture and livelihoods. It is home. Therefore, it is more than just a "commodity." While John Hantz's stated objective is to produce scarcity of the land as a commodity, residents living in the lower-income homes of post-industrial Detroit deal daily with scarcity of health, education and basic public services to which they are entitled. The transformation of these public goods into private "commodities," coupled with their scarcity has not resulted in any improvement for residents. Market demand and human needs are not the same, and one does not necessarily address the other. Driving up the price of land in underserved neighborhoods may well put the city on the road to gentrification, but it won't help solve the challenges facing the majority of Detroit's citizens.

There are many notable, socially and economically-integrated projects in Detroit that are already improving livelihoods, diet and incomes through urban farming. It is difficult to see how these can flourish in the shadow of a mega-project designed to price low-income people out of their own neighborhoods. While private sector initiatives need to be a part of any economic development strategy, unless the City's democratic public institutions can find positive ways to address Detroit's land question, it runs the risk of reproducing a classic land grab -- with all its disastrous consequences.

Tuesday, July 3, 2012

"Restoring the Neighbor back to the 'Hood Annual School Supply Family Fun Day"

Wednesday, June 27, 2012

D-Town Farm Friends - Feedom Freedom Rejuvenating Detroit's Eastside Vacant Lands!

Vacant Land - DETROITERS DESERVE A FAIR AND TRANSPARENT PROCESS TO PURCHASE CITY-OWNED VACANT LAND!

DBCFSN / DTownFarm Says: DETROITERS DESERVE A FAIR CHANCE TO PURCHASE CITY-OWNED VACANT LAND!

This year Garden Resource Program members will care for more than 100 acres of vacant land in the City of Detroit, saving the city hundreds of thousands of dollars in routine maintenance costs and investing at least as much in improvements like flowers, trees, benches, and fences. Despite these heroic efforts, gardeners and farmers that attempt to purchase the land they tend are routinely given the run around, made to wait years, and sometimes flat-out refused. One of the reasons that residents are denied sales is that City of Detroit zoning regulations do not allow for gardening and farming except for in backyards or similar accessory uses.

The Detroit City Planning Commission's Urban Agriculture Workgroup in partnership with the Detroit Food Policy Council, many city departments, and community leaders, has been working diligently to update zoning regulations and city code to allow for urban agriculture for more than two years. These zoning and code recommendations will be shared widely with the urban agriculture community as well as the general public at community forums throughout the summer and hopefully approved by City Council this fall. Despite this timeline and despite the fact that residents who have lovingly tended city owned vacant land for years are routinely denied the opportunity to purchase land, it appears as if the Mayor's Department is preparing to sell Hantz Farms hundreds of lots between the Fisher St., St. Jean, Mack, and Jefferson for $300/lot. To read a memo from The City of Detroit Planning Commission and learn more click here.

Why should Hantz Farms get preferential treatment? Please call City Council members today and request a fair and transparent process to purchase city owned vacant land. If you've been trying to purchase city owned land for gardening or farming call the Real Estate Department today to demand equal treatment!

City Council President Charles Pugh 313-224-4510, Council PresidentPugh@detroitmi.gov City Council President Pro Tem Gary Brown 313-224-2450, Councilmember Brown@detroitmi.gov

Council Member Saunteel Jenkins 313-224-4248, Council member jenkins@detroitmi.gov

Council Member Kenneth V. Cockrel, Jr. 313-224-4505, CockrelK@kcockrel.ci.detroit.mi.us

Council Member Brenda Jones 313-224-1245, bjones_mb@detroitmi.gov

Council Member André Spivey 313-224-4841, CouncilmanSpivey@detroitmi.gov

Council Member James Tate 313-224-1027, councilmembertate@detroitmi.gov

Council Member Kwame Kenyatta 313-224-1198, K-Kenyatta_MB@detroitmi.gov

Council Member Joann Watson 313-224-4535, WatsonJ@detroitmi.gov

City of Detroit Real Estate Department (313) 224-0953 or (313) 224-4195

Thursday, June 14, 2012

D-Town Farm: Detroit! - "What's The Most Important Meal Of Your Lifetime?" .

D-Town Farm: D-Town Farm: D-Town Farm: Detroit! - "What's The M...: D-Town Farm: D-Town Farm: Detroit! - "What's The Most Important... : "What's The Most Important Meal Of Your Lifetime?" D-Town Farm: D-Tow...

Saturday, June 9, 2012

D-Town Farm: D-Town Farm: Detroit! - "What's The Most Important...

D-Town Farm: D-Town Farm: Detroit! - "What's The Most Important...: "What's The Most Important Meal Of Your Lifetime?" D-Town Farm: D-Town Farm: Detroit! - "What's For Dinner?" - L... : D-Town Farm: Det...

Friday, June 8, 2012

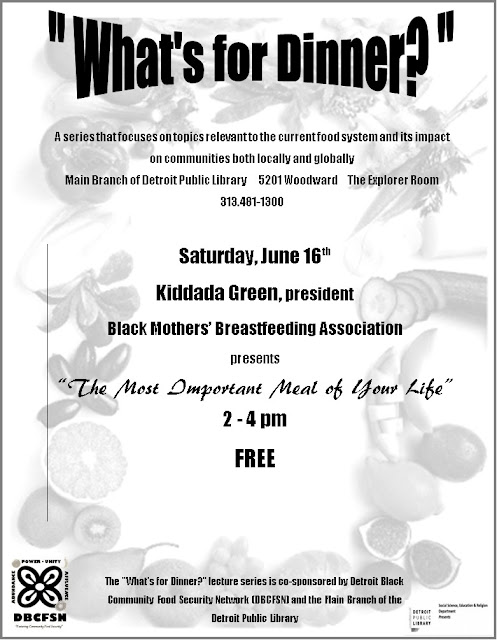

D-Town Farm: Detroit! - "What's The Most Important Meal Of Your Lifetime?" "MAIN LIBRARY, SAT., JUNE 16TH, 2012 2-4 PM"

|

| "What's The Most Important Meal Of Your Lifetime?" |

Monday, May 21, 2012

Wednesday, May 9, 2012

Sunday, April 15, 2012

D-Town Farm Presents A2Politico News Interview: Malik Yakini Is Helping...

D-Town Farm: A2Politico News Interview: Malik Yakini Is Helping...: Tuesday, April 10th, 2012 | Posted by A2 Politico Interview: Malik Yakini Is Changing the Face of the Food Landscape in Detroit ...

Wednesday, April 11, 2012

A2Politico News Interview: Malik Yakini Is Helping Change the Face of the Food Landscape in Detroit

Tuesday, April 10th, 2012 | Posted by A2 Politico

Interview: Malik Yakini Is Changing the Face of the Food Landscape in Detroit

by Hannah Wallace

When he was seven-years-old, Malik Yakini, inspired by his grandfather, planted his own backyard garden in Detroit, seeding it with carrots and other vegetables. Should it come as any surprise that today, Yakini has made urban farming his vocation? The Executive director of the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network (DBCFSN), which he co-founded in 2006, he is also chair of the Detroit Food Policy Council, which advocates for a sustainable, localized food system and a food-secure Detroit.

It’s well known that Detroit has been hard hit by the economic crisis—it’s unemployment rate is a staggering 28 percent—but it also has one of the most well-developed urban agriculture scenes in the country. Over the past decade, resourceful Detroiters and organizations such as DBCFSN have been converting the city’s vacant lots and fallow land into lush farms and community gardens. According to the Greening of Detroit, there are now over 1,351 gardens in the city.

I

spoke to Yakini (left), one of the leaders of Detroit’s vibrant food

justice movement, about the problem with the term “food desert,” how

Detroit vegans survive the winter, and what the DBCFSN is doing to

change the food landscape in Detroit. “We’re really making an effort to

reach beyond the foodies—to get to the common folk who are not really

involved in food system reform,” says Yakini.

I

spoke to Yakini (left), one of the leaders of Detroit’s vibrant food

justice movement, about the problem with the term “food desert,” how

Detroit vegans survive the winter, and what the DBCFSN is doing to

change the food landscape in Detroit. “We’re really making an effort to

reach beyond the foodies—to get to the common folk who are not really

involved in food system reform,” says Yakini.A2Politico: Tell me about the origins of the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network.

Malik Yakini: It grew out of some earlier work. I was principal of an African-centered charter school in the Detroit area called Nsoroma Institute Public School Academy. In 2000 we started doing organic gardening on a serious level and developed a food security curriculum. That initial garden evolved into something we called the Shamba Organic Garden Collective, where we had parents and teachers planting gardens in their backyards and in vacant lots next to their houses.

We had a team called the groundbreakers who would go out and till peoples’ gardens for them—because that was the most labor-intensive part. We had about 20 gardens spread out over the city as part of this collective. And as the work continued to grow, we were looking for a way to expand it and involve more people. Informally, the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network grew out of this work.

In February of 2006, I called together a group of 40 people who I knew were either gardeners, chefs, raw foodists—people who had some connection to food—for the purposes of starting the DBCFSN.

A2Politico: One of the main activities of the organization is to influence public policy. Is there a political leader in Detroit who has become a powerful advocate for the food justice movement and has helped push through laws that protect community gardeners and promote food security?

Malik Yakini: The one who has been most supportive has been councilwoman JoAnn Watson. And councilman Kwame Kenyatta has been supportive as well. In fact, it’s through JoAnn Watson that we were able to have the City Council approve the Food Security Policy that our organization wrote. She was able to give us the traction we needed to get the City Council to appoint members of the Detroit Food Policy Council.

A2Politico: What policy goals are the DBCFSN working on right now?

Malik Yakini: The big issue right now in Detroit is creating ordinances to regulate urban agriculture. There’s a big impediment and that’s a state law called “the Right to Farm Act.” Essentially it says no municipality has the authority to create ordinances that regulate agriculture within their jurisdiction, because of this state law that supersedes it. Just last week therewas a bill introduced to the Michigan house to exempt Detroit from the Michigan Right to Farm Act, which was passed in the early 1980s. It was passed to protect rural farmers from suburban sprawl and from complaints from people who were moving into rural areas where farming was taking place, who wanted it to be like a city. So the law was to protect the farmers, but it didn’t anticipate the urban agriculture movement we have now.

At this point, our policy work is primarily done through our involvement in the Detroit Food Policy Council. Our farm manager is a member of the Michigan Food Policy Council. So we are trying to move policy forward through our involvement in those two organizations.

A2Politico: Do you think there’s a chance the Michigan legislature will pass this bill?

Malik Yakini: It’s a question of building the proper coalition on a statewide level. We have to find a way to get enough Michigan state legislators to vote for that exemption. But that’s challenging because Michigan is a very large agricultural state. In fact, it has the greatest diversity of crops outside of California. But most of what is grown in Michigan, like every other state in the United States, is corn and soybeans. And so these corn and soy farmers are not the natural allies of the sustainable ag folks in Detroit. It’s gonna take some networking across traditional interests in order to build the kind of support politically that we’d need to get an exemption.

Flint and Grand Rapids have very large urban ag movements, too, and they’re handcuffed in the same way. So there are some natural allies out there. But in order to move this thing forward we have to have some allies in rural Michigan—the traditional farmers.

A2Politico: Does that mean that urban farmers in Detroit are technically defying the law right now?

Malik Yakini: There’s a woman on the Food Policy Council who is an employee of the City Planning Commission. She says there are some things that are illegal and some things that are unlawful. It’s illegal to have farm animals like cows in the city of Detroit—there’s a law prohibiting that. But there are other things like bees that the law doesn’t speak to specifically. So there’s no law that permits it and there’s also not a law that prohibits it. It’s not lawful but it’s not illegal. So we’re kind of caught in this grey area right now.

It’s been estimated that Detroit has about 6,000-10,000 acres that are vacant—that’s about a third of the city. So you have a lot of commercial interests beginning to look at Detroit as a place to do agriculture. Because the city doesn’t have the ability to regulate it right now, we don’t have the ability to say to these large commercial interests that we don’t feel that this scale of agriculture is appropriate for Detroit. Getting the exemption from the Right to Farm Act would allow Detroit to define what is appropriate in terms of scale and in terms of things like composting.

A2Politico: What about policy on the national level. Does the DBCFSN have any position on the farm bill?

Malik Yakini: Several of us have been involved in webinars and meetings to bring us up to speed on the farm bill. But we haven’t actively taken a position as a group.

We’re more focused on local policy. After studying the farm bill over the last several months, I have a concern about what it takes to build the type of support nationally, across various interests, to get anything passed in the farm bill. It’s much easier to build that level of consensus on a local or state-wide basis.

I think big ag will continue to get billion dollar subsidies. Some of the things that were added in the last farm bill were good: Our organization got a hoop house from the USDA as a result. But when you look at a hoop house that cost $8,000 and maybe there are 5-10 of ‘em in Detroit, that’s $40,000 to $80,000. But then you’re looking at billions of dollars that are going to these folks who are growing corn and soybeans.

So really, if we want to have a major impact on the food system in the United States, the paradigm has to be shifted. So that sustainable agriculture is incentivized and this unsustainable model of industrial farming is dis-incentivized. The best way to do that is through money. Of course, that is a big fight because the food lobby is one of the most powerful lobbies that exists. And I really haven’t heard answer of how you build the level of power, how you galvanize that level of support, on a national level.

A2Politico: The DBCFSN has a “What’s for Dinner?” lecture series. What speakers have you had and what are they about?

Malik Yakini: This year we had four lectures. The first was called “Is my garden legal?” by Kathryn Underwood, the woman who is on the Detroit Food Policy Council. She spoke about the laws or lack of laws regulating agriculture in Detroit. The second lecture was a guy named Kilindi Iyi and he’s a mycologist. His was on adding mushrooms to your garden and the technologies of growing mushrooms. The third lecture was the board president of our organization, Ife Kilimanjaro, and it dealt with the global food shortage and how that is a man-made phenomenon how it has been manipulated through these multinational companies that are are controlling much of the food supply. The final lecture was one I did on the impact of global warming on agriculture.

So this lecture series—as well as some of the other things we do—is geared towards raising public consciousness. Because we realize that it’s not just a question of greater access to food. But people have to have knowledge about the food, and have to have some understanding about why sustainable growing is better than the industrial food system that provides most of the food. They have to have some understanding about food culture. Because much of our traditional food culture has been lost over the past generation, due to the rush towards convenience in the post World War II period, and then the fast food proliferation which occurred in Detroit and other places throughout the country. Our families today rarely sit down and eat a meal that’s prepared from scratch. So there’s a lot of education that has to go on in order to support the growing of fresh produce. And creating markets in which to sell it. We have to increase demand at the same time as we’re increasing access.

A2Politico: Is D-Town Farm the DBCFSN’s only garden? Or do you have others?

Malik Yakini: We just have one location. We started out initially with two acres and we currently have seven acres—so it’s a pretty large project. We’re trying to stay focused and not have various locations around the city. Frankly we don’t have the capacity to manage that. Even managing the seven acres we have now is challenging!

We consider ourselves to be a model. Rather than trying to start gardens all around the city, what we’re doing is creating a learning institution where people who are interested in doing this work can come and learn various techniques and strategies that they can take back to their neighborhoods. So we see ourselves as a catalyst.

A2Politico: So the produce that’s grown at D-Town Farm—is it sold there at a farm stand or at Eastern Market?

Malik Yakini: We sell it at Eastern Market and also at a few farmers’ markets. We also sell to a few restaurants. We’re working on a project called “Take it to the Marketplace” that will put some of our products in grocery stores. It’ll be a producers’ co-op that we’ll be part of and we’ll invite other local food entrepreneurs to be part of. But it will sold under the D-Town brand. And we’ll collectively market and promote those products, and collectively distribute those products. So that’s our next move: to have locally grown options available at stores that people normally shop at.

A2Politico: Speaking of grocery stores, you said something interesting at the Community Food Security Coalition conference in Oakland: that implicit in researcher Mari Gallagher’s definition for “food desert” is the notion that grocery stores are the only solution to food deserts. In fact, what she and others including you stress is that multiple solutions are needed—farmers’ markets, food co-ops, urban farms. But don’t Detroit residents—even those who buy their food from D-town Farm—rely on grocery stores in the winter? Even with hoop house technology, you can’t possibly grow enough produce in the winter months for people to be food secure—can you?

Malik Yakini: Not at all. We don’t even grow enough in the ground in the summer to be self-sufficient. We’re producing a very small amount of the produce consumed in Detroit—probably less than 1 percent. We are at the embryonic stages. We think we have much greater capacity. But we’re nowhere near that point right now.

People are accustomed to going to grocery stores to buy food and they’re used to these large, pretty pieces of produce. Often, organic food is not as large and sometimes it has flaws. So we have to re-educate people about the aesthetics of food and the nutritional value of food, at the same time as we educate people about the value of eating whole foods.

We’re not self-sufficient even in the summer time—less so in the winter. We are producing food in the winter using hoop house technology, but of course you can only grow limited crops in the winter using hoop houses unless you have some external heating source. People are primarily growing salad greens, collards, kale, and things like that. They clearly aren’t growing peppers, tomatoes, and squash in the winter in hoop houses.

A2Politico: Without a full-service grocery store, where do you find sustainable dairy, meat, or bread? Does Detroit have any meat CSAs?

Malik Yakini: Because I’m a vegan, I haven’t done a lot of investigation about sources for eating meat and dairy. Although that’s my personal dietary preference, that’s clearly not the dietary preference of the majority of the people in Detroit. So since the majority of people do eat meat, we need to find ways of finding high quality meat at affordable prices. I’m very ignorant about what those options are, but that’s an area I intend to educate myself about in the near future.

A2Politico: But even as a vegan, it must be a challenge to find enough healthy food in Detroit in the winter. Do the locally-run bodegas in town—the “party stores”—have any fresh produce?

Malik Yakini: Unfortunately, many of us, particularly those of us who are trying to eat organic foods, have to leave the city to find those. I’m privileged enough to have an automobile. [Note: 1/5th of all Detroit households are car-less.] I’m able to drive the couple of miles from my house to get to Ferndale, where they have food outlets that sell organic food. They do sell some local produce but of course during the winter that selection is very limited. And so although I am dedicated to eating local foods, I’m not able to do that to the extent that I’d like to during the winter time.

A2Politico: I read an article that asserted that Detroit and Cleveland have plenty of corner stores, many of which sell produce. The USDA overlooks such stores when they designate a neighborhood a food desert. (They define supermarkets as grocery stores with at least $2 million in annual sales.) But don’t these so-called “fringe stores” sell mostly processed food, liquor and cigarettes?

Malik Yakini: There are small grocery stores in Detroit. Mari Gallagher’s 2007 study said there were something like 1,075 food outlets in the city of Detroit. The vast majority, though, are convenience stores or what we call party stores. The problem is that far too many of them sell food that is of an inferior quality, sometimes at inflated prices. And the sanitary conditions in the stores often leave something to be desired. I don’t want to paint with too broad a brush, because there are some very good independently-owned grocery stores in Detroit. A few. So I don’t want to leave the impression that they’re all terrible. Many of them are terrible. But even the decent ones aren’t selling organic produce. And for me, eating organically is very important.

A2Politico: Your friend Malik Shabazz of the Marcus Garvey movement has been videotaping some of the blatant health violations at “party stores” such as rat feces, and is reporting them to the Department of Public Health.

Malik Yakini: He’s also finding meats that have another label placed over the expiration label. He’s finding stores that are selling alcohol to minors. He’s documenting all of these things. His organization creates the kind of pressure and public scrutiny that’s needed to close down drug houses, too. It’s part of an overall effort to create a higher quality of life in Detroit’s African American community.

A2Politico: In Oakland, you cautioned that racism is prevalent in the food movement—that some white food activists will come into an African American community and tell them what to do. Can you give an example of a white food justice organization in Detroit who is a good ally of the DBCFSN, who works with you in a collaborative way?

Malik Yakini: The main ally we have is Earthworks Urban Farm. The manger there is Patrick Crouch. We do quite a few things together including participating in the “Undoing Racism in the Detroit Food System” initiative. They are probably our best predominantly white allies.

A2Politico: One of the goals of the DBCFSN is to promote healthy eating habits amongst Detroit’s youth. Any tips on how to do this? Kids can be tough critics.

Malik Yakini: When children are involved in growing food, they feel a sense of ownership. Like, “I grew that carrot, I planted those seeds.” That’s a big incentive right there. But also just bringing in fresh greens and having the kids taste them. Typically they enjoy it—they like it.

We have a youth program called Food Warriors youth development program that functions at Nsoroma. Also, there is a food security curriculum that’s woven into the fabric of the school. Every teacher has to have one lesson per week that has a food security tie-in. We look at food security in a very broad sense, not just in terms of providing access to food but we look at all aspects of the food system. With some of the younger children, rather than inundate them with a lot of theory, their food security lessons are more hands on. Preparing things, tasting them. Exposing them to foods that they don’t normally eat.

Healthy eating is part of the culture at the school—and it has been for some time. Gum, candy, and soda pop are not allowed in the building at all—either by students, staff, or parents. That’s been a long-standing policy. There’s a catering company that provides lunch every day. So we have whole grains—no white rice is served—it’s always brown rice. There’s no red meat served. And so we’ve created a cultural environment that is supportive of healthy eating. So the Food Warriors are building on a culture that already exists in the school.

A2Politico: What about public schools in Detroit? Are there people putting pressure on them to improve their food?

Malik Yakini: The food service director of Detroit Public Schools, Betti Wiggins, is very progressive. She was recently elected to the Detroit Food Policy Council and she’s very active in the food movement. She has reached out to local growers. Of course she’s working for a bureaucracy that slows down what she’d like to do. But there couldn’t be a better person in place pushing for this to happen.

She is involved in the farm-to-school movement and has piloted that in several schools in Detroit, and has encouraged several schools to start gardens. So she is a very strong ally in this movement.

A2Politico: What do you think of entrepreneur John Hantz, and this ambitious plan he has to create “the largest urban farm” in Detroit?

Malik Yakini: That is the inevitable question. All interviews lead to that question.

I find it to be problematic for several reasons. The first reason is because the city is 77% African American (according to the latest Census Data), and the key players in the Hantz project are white men. That’s problematic.

Secondly, they are not committed to organic agriculture. They propose some type of mixture of the traditional industrial farming model and sustainable techniques.

Thirdly—and most alarmingly—they don’t have any sense of using urban agriculture to empower communities. They are driven by the profit motive. The current urban ag movement is clearly steeped within the social justice movement and clearly is trying to empower people, communities, and community organizations. And none of that is on the radar of the Hantz project. So that is very troubling.

Although Mr. Hantz is proposing this very large farm, what a lot of people don’t know is that he’s proposing that only ten percent of what he grows is produce. The rest is Christmas trees! Most people think he’s going to have thousands of acres of tomatoes and peppers and lettuce, but that’s not the case.

Mr. Hantz has also said that really what he’s trying to do is create scarcity, thereby driving up the value of the land. At a public forum, someone said to him, “Well that sounds like a land grab.” And he said, “Yes, it is a land grab.” That’s another problem. There are major questions around use and ownership of land. And how land serves the common good as opposed as trying to serve the interests of wealthy individuals who are trying to make a profit.

A2Politico: Has he reached out to the black community in Detroit in any way?

Malik Yakini: After much criticism, there has been some reaching out to community members. But it seems to be an afterthought, after he received so much criticism. He’s also made overtures to me. I’ve been involved in a couple discussions about trying to sit down with him to understand more fully what he wants to do.

I have a good relationship with Mike Score, who is the president of Hantz Farms. Mike is the person who is leading the farm effort right now. He’s a legitimate farmer and an honorable human being with a very high level integrity. He and I have talked about trying to set up a meeting with Mr. Hantz and some of the key people in the urban ag movement. But Hantz has been resistant to meeting with a group of people.

A2Politico: You were awarded a two-year fellowship with the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy. Do you mind my asking how you’re spending the $35,000 stipend? What project or projects are you working on?

Malik Yakini: I proposed a project called Be Black & Green. What I’m doing is video documentation of black farmers, gardeners and food activists throughout the country. I just posted an interview with David Hilliard (of the Black Panthers) that I shot in Oakland, and I have five others in the can that I’ll be posting soon. What I’m doing is creating a network of black farmers, gardeners and food activists so they can know each other. I’m also raising the profile of black farmers, gardeners, and food activists in the larger food movement.

We want to assert that black people have always been involved in agriculture in this country and we’ve always been involved in sustainable agriculture. And that we have as much claim to this movement as anybody else does. And so by telling these stories and really allowing others to tell their own stories, and raising the profile of of black people doing this work, I hope to help people understand the role that we play in this movement historically.

A2Politico: It’s out of the bag: kale is your favorite food. What’s your preferred way of preparing it?

Malik Yakini: Raw kale salad. I’m just addicted to it. I serve it with a special dressing: toasted sesame seed oil, nutritional yeast, cayenne pepper—those are three of the main ingredients. I can’t tell you the rest of the ingredients, but I can say that people really seem to like it.

A2Politico: What’s your definition of food justice?

Malik Yakini: Food justice is people being treated justly by all of the venues that they interact with to obtain food. The other part of food justice has to do with economic justice: that when people spend money on food, they need to derive some benefits from the money that they spend beside just trading food for money.

The money that they spend on food needs to enrich their community. In too many cases, we have wealth extraction strategies—where people spend money in their communities on food and money is taken out of their communities and creates jobs and wealth in other communities. So part of food justice is circulating the money that people spend on food in their community for their own benefit. It also has to do with simple things like people being spoken to respectfully at the places that they go to purchase food, with their human dignity being upheld. Having equal access to good food sources—that’s a big part of food justice. So I would say, the access piece is key, upholding peoples‘ dignity is key, and the economic justice part of it is key.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)